October is National Bullying Awareness Month. Every year I hope for improvement in the landscape of this fierce disruptor, and especially for my colleagues within healthcare. Yet, the incidence of incivility keeps rising. The post-pandemic disruption continues with workforce shortages, attrition and retention challenges, staff burnout, and a slew of occupational hazards. What began decades ago with a few posturing practitioners and nurses who ate their young remains an interprofessional sport that every discipline plays, and nobody gets to sit out.

Psychological Safety and Workplace Bullying

Bullies take chronic hits at your psychological safety. Their goal is to make you feel inefficient, ineffective, and incapable of performing your role. They mess with your perception of whether it is safe to take interpersonal risks within your appointed role at work, such as in taking initiative to advocated for patient care and treatment. They sabotage your sense of self and thus confidence so that you may fail to follow through on critical communications with team members. Ultimately, the quality of your workplace performance is questioned along with your mental health.

Bullies are ever-present across sectors and can invade your volunteer experiences, such as roles for a professional association or other efforts. An activity you engaged in for sheer enjoyment, becomes as arduous to engage in as any professional role. Ultimately your occupational health, mental health, and safety are all compromised. Every member of healthcare’s valued interprofessional workforce is impacted:

Bullying and incivility incidence have ramped up from DEIB’s lens, and impacting:

Negative outcomes are plaguing quality improvement and risk management specialists across practice settings. Incivility by practitioners leads to medical errors >75% of the time, and resulting in death >30% of the time. The workforce is also at elevated risk of trauma, and especially suicide from repeated psychological assaults:

- Suicidal ideation: >30% of victims (of bullying)

- Suicide: Victims 2X as likely to take their own life compared to those not exposed

Bullying’s Advancing Dimensions

Bullying is a consistent pattern of repeated, health-harming mistreatment of one or more members of the workforce, marked by abusive conduct that is threatening, humiliating, or intimidating. Work is delayed, sabotaged, and obstructed. These are impediments that NO professional can afford in the fast-paced industry. We’re not talking about random episodes when someone feels crispy around the edges or has a bad day, but rather a chronic and recurrent pattern of behaviors that somehow devalues others.

Gaslighting, Mobbing, and Remote Bullying, OH MY!

Bullying has morphed into assorted dimensions. Gaslighting occurs when a colleague ignites the gas by tossing out an inflammatory implication that forces you or others to question your actions or ability to do the job. The bully fans the fire by ongoing attacks; they may challenge your memory of events, such as implying that you ‘forgot’ to follow up on dialogues with a patient’s family or member of the care team. There may be comments to other colleagues about your bouts of ‘memory loss’. Imagine, being approached by staff or patient families to verify if you completed documentation that you clearly recall doing. Even you start to question the quality of your work performance, especially as your reputation and job performance are at issue. Six types of gaslighting are:

- Countering: Challenging someone’s memory

- Denial: Refusal to take responsibility for actions

- Diverting: Changing a discussion focus by questioning someone else’s credibility

- Stereotyping: Generalizing through negative or discriminatory views of a person’s race, ethnicity, sexuality, nationality, or other cultural nuance.

- Trivializing: Disregarding when someone feels minimized by what is said and devaluing the impact

- Withholding: A bully pretends to not understand a conversation and refuses to listen to another person’s view. That person ends up doubting themself.

Mobbing is bullying on steroids and occurs when multiple staff target one or more personnel. Almost 50% all bullying incidents involve mobbing with 54% of primary care professionals exposed to this type of incivility on at least one occasion. Perhaps, a new director of Case Management at an MCO changes the job description to require all new hires to possess case management certification; current employees must be certified by the end of that calendar year. Staff view this requirement as an undue hardship and become frustrated. The rumor mill ensues: ‘The quality of the work isn’t important, only if we can pass a test.’; ‘she doesn’t care about us.’ The mob works to discredit the boss and push her out the door. Staff may view a new colleague as not fitting in, whether because of being in a different age group, professional discipline, as well as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation or other cultural nuance. As a result the staff member does not feel safe, seen, heard, or valued.

Remote bullying has risen amid the increase of virtual roles. Some 43% of employees were exposed to remote bullying experiences:

- 50% of incidents during virtual meetings

- 10% via email interactions, and

- 6% during group emails and chats.

What YOU Can Do to Promote Psychological Safety!

Bullies are insidious and invasive in their efforts. BUT, here’s their dirty secret and biggest misstep! BULLIES target the most ethical, hard-working, and high-performing individuals in an organization. If you’ve been bullied, it means you’re more powerful than you’ve ever imagined, as you’re a threat to the bully and their ineptitude.

Tackling bullying involves strategy:

- Intervene early: Don’t let a precedent be set and address the behavior directly

- Don’t react to the bully: ‘Take 10’ to breathe, consider, and define an approach

- Document each incident: Date, time, witnesses, and who you discussed it with.

- Don’t let the bully isolate you: Keep engaged with peers and those who trust your savvy.

- Set limits on negative behaviors you will allow: We may let small things go, but stay vigilant.

- Don’t share lots of personal details at work: This info will be used against you

- Take time to recharge from incidents: Mental health days or vaca help restore your resilience

- Seek Support: Peer support and mental health support are MUSTS; one may potentially need independent legal support!

- Put your best professional self forward: Bullies thrive on the weakness of others, so keep showing that best version of yourself

- Approach bullying as a work project: Being methodical keeps you in control. Assess financial costs of staff departures related to bullying, and the ROI of psychological safety and other workforce retention strategies

Those steps and other ways to advance each above strategy live in Chapters 3 and 6 of The Ethical Case Manager: Tools and Tactics. The book’s content:

- Defines terms associated with workplace bullying

- Discusses how workplace bullying impacts physical and mental health

- Aligns workplace bullying, quality of care, and patient safety

- Recognizes the “Bullying Recipe” within organizations

- Examines how the practice culture of professional education impacts incidence

- Explores the incidence across the DEIB landscape

- Identifies types of organizational culture that contradict workplace bullying

- Discusses leadership styles to impact workplace bullying in organizations

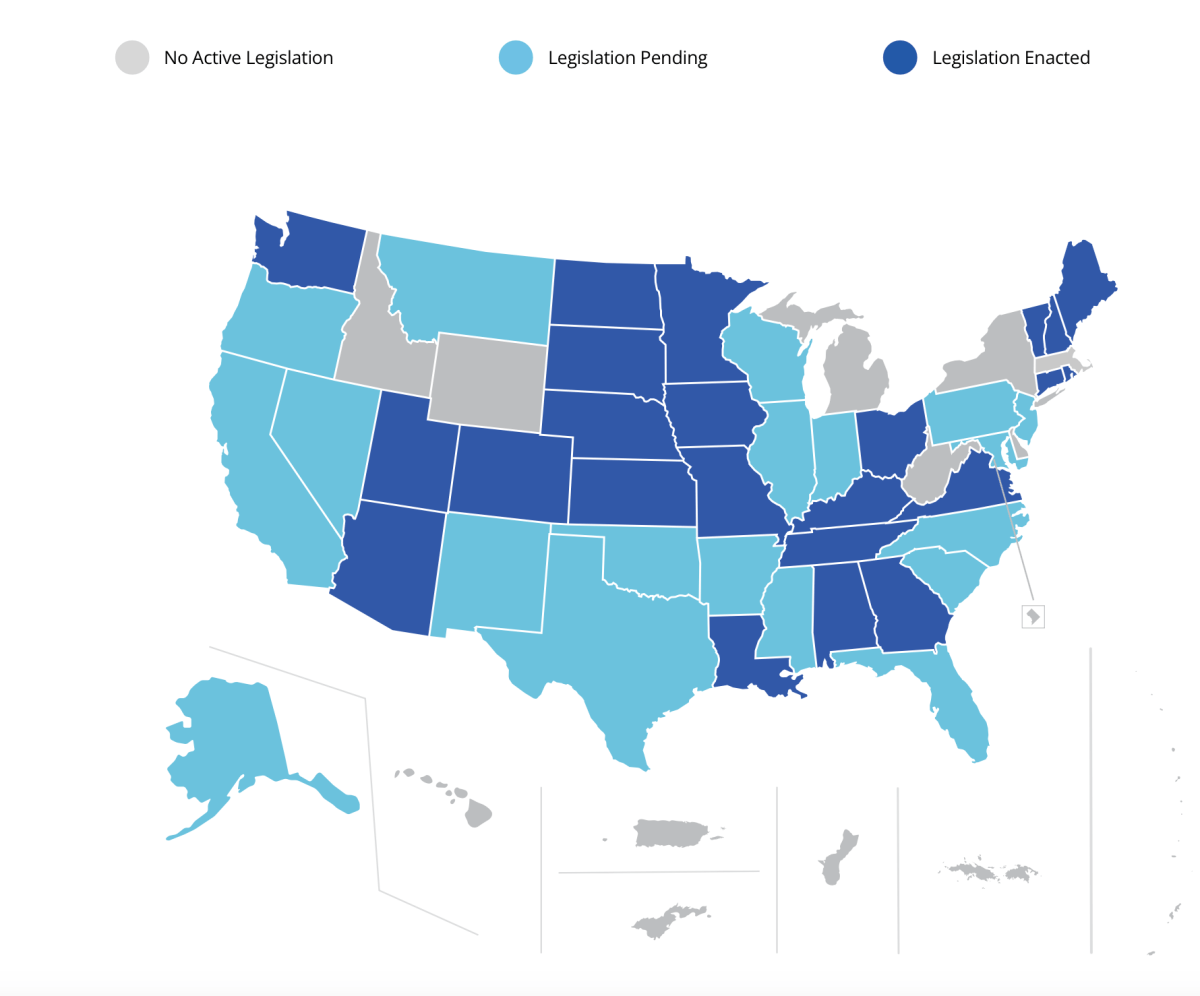

- Identifies legislation and professional initiatives to combat workplace bullying

- Explores how bullying impedes the ethical performance of case managers

- Offers quality monitoring tools to address unprofessional behaviors

- Informs you how to calculate costs of workplace bullying for your organization

REMEMBER

Keep Ellen’s Ethical Mantras close by:

- We deserve respect.

- We deserve to feel safe.

- We deserve not to feel trapped in a toxic workplace.

- We deserve to have our knowledge and expertise valued.

- We deserve to have confidence that all are accountable for their actions.

- We deserve to be able to confront workplace bullying without fear of retribution.

October is National Bullying Awareness Month. Every year I hope for improvement in the landscape of this fierce disruptor, and especially for my colleagues within healthcare. Yet, the incidence of incivility keeps rising. The post-pandemic disruption continues with workforce shortages, attrition and retention challenges, staff burnout, and a slew of occupational hazards. What began decades ago with a few posturing practitioners and nurses who ate their young remains an interprofessional sport that every discipline plays, and nobody gets to sit out.

Psychological Safety and Workplace Bullying

Bullies take chronic hits at your psychological safety. Their goal is to make you feel inefficient, ineffective, and incapable of performing your role. They mess with your perception of whether it is safe to take interpersonal risks within your appointed role at work, such as in taking initiative to advocated for patient care and treatment. They sabotage your sense of self and thus confidence so that you may fail to follow through on critical communications with team members. Ultimately, the quality of your workplace performance is questioned along with your mental health.

Bullies are ever-present across sectors and can invade your volunteer experiences, such as roles for a professional association or other efforts. An activity you engaged in for sheer enjoyment, becomes as arduous to engage in as any professional role. Ultimately your occupational health, mental health, and safety are all compromised. Every member of healthcare’s valued interprofessional workforce is impacted:

Bullying and incivility incidence have ramped up from DEIB’s lens, and impacting:

Negative outcomes are plaguing quality improvement and risk management specialists across practice settings. Incivility by practitioners leads to medical errors >75% of the time, and resulting in death >30% of the time. The workforce is also at elevated risk of trauma, and especially suicide from repeated psychological assaults:

- Suicidal ideation: >30% of victims (of bullying)

- Suicide: Victims 2X as likely to take their own life compared to those not exposed

Bullying’s Advancing Dimensions

Bullying is a consistent pattern of repeated, health-harming mistreatment of one or more members of the workforce, marked by abusive conduct that is threatening, humiliating, or intimidating. Work is delayed, sabotaged, and obstructed. These are impediments that NO professional can afford in the fast-paced industry. We’re not talking about random episodes when someone feels crispy around the edges or has a bad day, but rather a chronic and recurrent pattern of behaviors that somehow devalues others.

Gaslighting, Mobbing, and Remote Bullying, OH MY!

Bullying has morphed into assorted dimensions. Gaslighting occurs when a colleague ignites the gas by tossing out an inflammatory implication that forces you or others to question your actions or ability to do the job. The bully fans the fire by ongoing attacks; they may challenge your memory of events, such as implying that you ‘forgot’ to follow up on dialogues with a patient’s family or member of the care team. There may be comments to other colleagues about your bouts of ‘memory loss’. Imagine, being approached by staff or patient families to verify if you completed documentation that you clearly recall doing. Even you start to question the quality of your work performance, especially as your reputation and job performance are at issue. Six types of gaslighting are:

- Countering: Challenging someone’s memory

- Denial: Refusal to take responsibility for actions

- Diverting: Changing a discussion focus by questioning someone else’s credibility

- Stereotyping: Generalizing through negative or discriminatory views of a person’s race, ethnicity, sexuality, nationality, or other cultural nuance.

- Trivializing: Disregarding when someone feels minimized by what is said and devaluing the impact

- Withholding: A bully pretends to not understand a conversation and refuses to listen to another person’s view. That person ends up doubting themself.

Mobbing is bullying on steroids and occurs when multiple staff target one or more personnel. Almost 50% all bullying incidents involve mobbing with 54% of primary care professionals exposed to this type of incivility on at least one occasion. Perhaps, a new director of Case Management at an MCO changes the job description to require all new hires to possess case management certification; current employees must be certified by the end of that calendar year. Staff view this requirement as an undue hardship and become frustrated. The rumor mill ensues: ‘The quality of the work isn’t important, only if we can pass a test.’; ‘she doesn’t care about us.’ The mob works to discredit the boss and push her out the door. Staff may view a new colleague as not fitting in, whether because of being in a different age group, professional discipline, as well as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation or other cultural nuance. As a result the staff member does not feel safe, seen, heard, or valued.

Remote bullying has risen amid the increase of virtual roles. Some 43% of employees were exposed to remote bullying experiences:

- 50% of incidents during virtual meetings

- 10% via email interactions, and

- 6% during group emails and chats.

What YOU Can Do to Promote Psychological Safety!

Bullies are insidious and invasive in their efforts. BUT, here’s their dirty secret and biggest misstep! BULLIES target the most ethical, hard-working, and high-performing individuals in an organization. If you’ve been bullied, it means you’re more powerful than you’ve ever imagined, as you’re a threat to the bully and their ineptitude.

Tackling bullying involves strategy:

- Intervene early: Don’t let a precedent be set and address the behavior directly

- Don’t react to the bully: ‘Take 10’ to breathe, consider, and define an approach

- Document each incident: Date, time, witnesses, and who you discussed it with.

- Don’t let the bully isolate you: Keep engaged with peers and those who trust your savvy.

- Set limits on negative behaviors you will allow: We may let small things go, but stay vigilant.

- Don’t share lots of personal details at work: This info will be used against you

- Take time to recharge from incidents: Mental health days or vaca help restore your resilience

- Seek Support: Peer support and mental health support are MUSTS; one may potentially need independent legal support!

- Put your best professional self forward: Bullies thrive on the weakness of others, so keep showing that best version of yourself

- Approach bullying as a work project: Being methodical keeps you in control. Assess financial costs of staff departures related to bullying, and the ROI of psychological safety and other workforce retention strategies

Those steps and other ways to advance each above strategy live in Chapters 3 and 6 of The Ethical Case Manager: Tools and Tactics. The book’s content:

- Defines terms associated with workplace bullying

- Discusses how workplace bullying impacts physical and mental health

- Aligns workplace bullying, quality of care, and patient safety

- Recognizes the “Bullying Recipe” within organizations

- Examines how the practice culture of professional education impacts incidence

- Explores the incidence across the DEIB landscape

- Identifies types of organizational culture that contradict workplace bullying

- Discusses leadership styles to impact workplace bullying in organizations

- Identifies legislation and professional initiatives to combat workplace bullying

- Explores how bullying impedes the ethical performance of case managers

- Offers quality monitoring tools to address unprofessional behaviors

- Informs you how to calculate costs of workplace bullying for your organization

REMEMBER

Keep Ellen’s Ethical Mantras close by:

- We deserve respect.

- We deserve to feel safe.

- We deserve not to feel trapped in a toxic workplace.

- We deserve to have our knowledge and expertise valued.

- We deserve to have confidence that all are accountable for their actions.

- We deserve to be able to confront workplace bullying without fear of retribution.