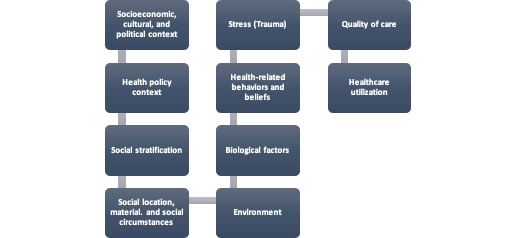

News outlets were flush with reports last weeks of the latest happenings in the Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) space. The top stories were all aligned with press releases from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) touting efforts to address “Systemic Inequities” as part of their, 2022 Strategic Plan.

The bold effort encompassed:

- Release of the Inpatient Prospective Payment System 2023 Rule, including the health equity trifecta of:

- Request for public comment over the next 60 days on means to enhance and/or standardize SDoH documentation through data collection of inpatient claims and metrics that analyze disparities across programs and policies, including a request for information related to homelessness reported by hospitals on Medicare claims

- Update of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) to improve performance for socially at-risk populations, and

- Implementation of “birthing friendly” hospital designations to improve maternal health outcomes and reduce associated morbidity and mortality.

- Commitment by (CMS) to mitigate health disparities through efforts aligned with Executive Order 13985, Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities through the Federal Government.; all CMS offices are to embed health equity into the core of their work:

- Aimed to better identify and respond to inequities in health outcomes,

- Barriers to coverage, and

- Access to care.

The means to achieve these efforts included a robust plan that looks great on paper:

- Close gaps in health care access, quality, and outcomes for underserved populations.

- Promote culturally and linguistically appropriate services Build on outreach efforts to enroll eligible people across Medicare, Medicaid/CHIP and the Marketplace.

- Expand and standardize the collection and use of data, including race, ethnicity, preferred language, sexual orientation, gender identity, disability, income, geography, et al. across CMS programs.

- Evaluate policies to determine how CMS can support safety net providers

- Ensure engagement with and accountability to the communities served by CMS in policy development and program implementation

- Incorporate screening for and promote broader access to health-related social needs, including wider adoption of related quality measures, coordination with community-based organizations, and collection of social needs data in standardized formats

- Ensure CMS programs serve as a model and catalyst to advance health equity through our nation’s health care system, including with states, providers, plans, and other stakeholders.

- Promote the highest quality outcomes and safest care for all people using the framework under the CMS National Quality Strategy.

Yet, my antennae shot up while reading one CMS quote:

“ The agency will bring together healthcare stakeholders—including payers—to promote implementing a health equity strategy. The first meeting will address achieving health equity in maternal healthcare, specifically. It will occur during the summer of 2022.”

Time to hurry up and wait. It seems the health equity strategy is not totally defined: shocking, I know! My elation at seeing formal acknowledgement and attention to, systemic inequities, was quickly dashed. Advancing legislation and funding for the SDoH alone will not fully mitigate the gaps in care. Most experts agree these well-intended efforts will fail, unless the systemic biases that have created and perpetuated the SDoH are also addressed.

CMS will have to do better than introducing a health equity pillar with strategic language. On the other hand:

- YES, for the $226.5 M announced this week via HHS and HRSA for Community Health Worker training; build that segment of the workforce. The fiscal and clinical impact of CHWs is massive, enhancing discharge planning outcomes, enhancing treatment and resource access to the most at-risk patients and populations, which bridges serious gaps in care.

- Develop, fund, and maintain the data exchange infrastructure:

- Expand and implement more end to end, social risk analytics and assessment programs like those in play by UniteUs, Socially Determined., and 3M.

- Expand ICD-10 CM Z codes and approve their reimbursement. I cloud the issue with logic, though reimbursing organizations for the blatant impact of the SDoH and MH on healthcare utilization (e.g., length of stay, ED admissions, readmissions, costs) would greatly enhance revenue coding and capture by healthcare organizations. Organizations will use the codes if there is direct fiscal incentive to do so. GO GRAVITY PROJECT !

- Grow technology programs that directly support my hospital case management colleagues in assessing, referring, and directly connective patients to needed resources, such as FindHelp.

- Expand, Food is Medicine programs nationwide, along with the means to assess and directly link patients to necessary nutritional resources GO FarmBoxRx, FoodSmart!

- Grow funding to Community-based organizations, and safety-net programs, as in community action agencies, neighborhood health clinics, and federally qualified health centers: these are the folks in the trenches!

There was a time when, where CMS went (in terms of reimbursement, programming, and funding) the rest of the industry followed. Yet has this trend shifted? Many have heard me say, “Communities take care of their own”; that is especially true in attaining health equity. Was this latest effort by CMS enough? In time, outcomes will tell the story, but for now, industry stakeholders have stepped up to lead the efforts for their communities, and running ahead of pack.

Your comments are valued so feel free to add them below.