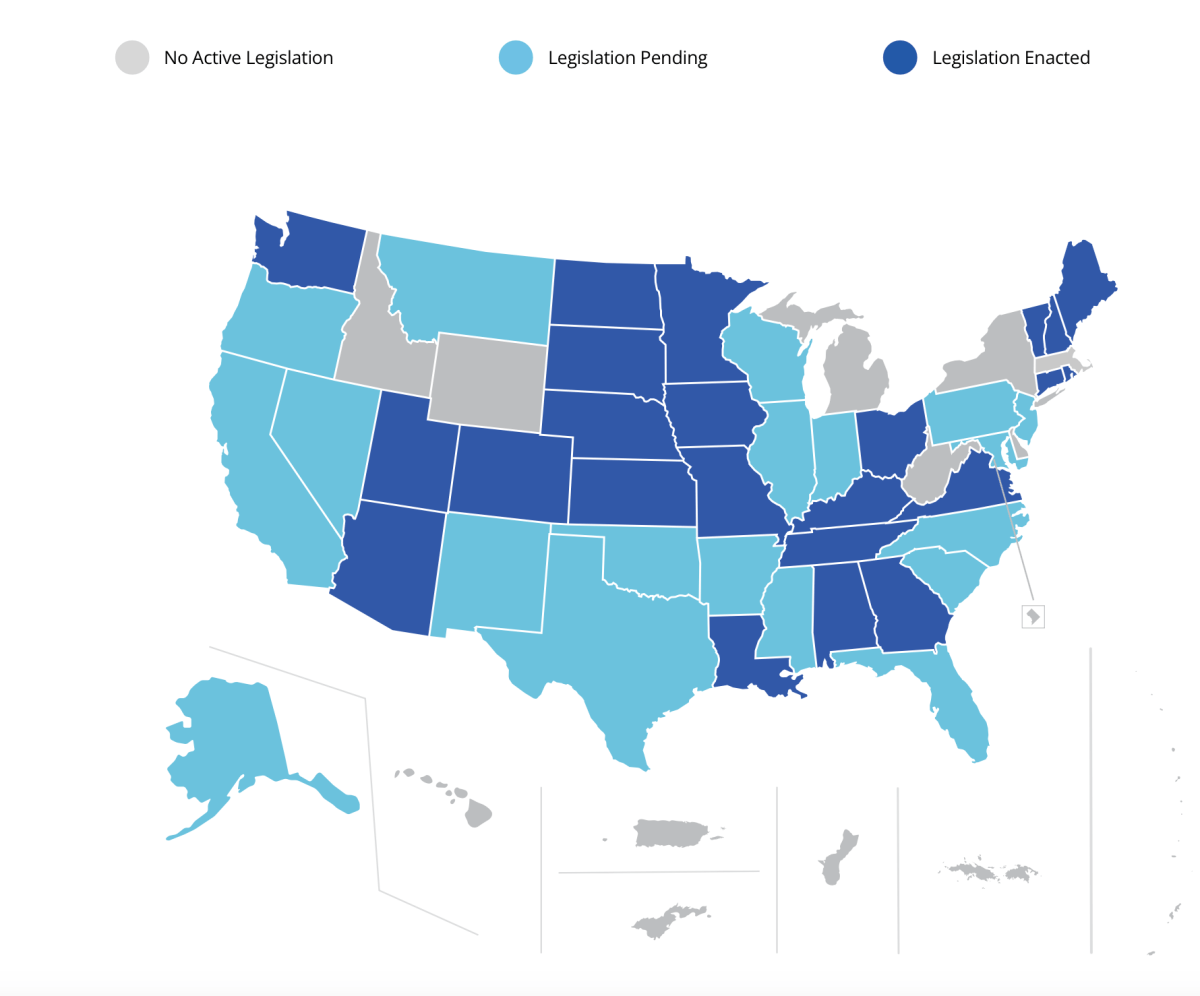

As the current state legislative session is in full swing, I thought it was a good time to review the status of the Social Work Compact. We entered the 2025 session with 24 states previously passing the Compact: Alabama, Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Ohio, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, and Washington State. The Social Work Licensure Compact Commission is advancing the formal infrastructure with the current target date for implementation by Fall 2025.

As of the time of this writing, 18 more states have stepped up with new legislation to advance the compact further: Alaska, California, Florida, Illinois, Indiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, Wisconsin.

The Compact Landscape

There is considerable workforce commitment to advance compacts across every discipline. Contributing factors include workforce mobility and for their patient populations, along with telehealth popularity. The current state tally for compact passage across other professions includes:

- Interstate Medical Licensure Compact (IMLC): 30 states

- Nurse Licensure Compact (NCL): 43 states

- Occupational Therapy Licensure Compact: 32 states

- PsyPact: 42 states

- Physical Therapy Compact: 32 states

A Clear and Present Danger

Let’s get one elephant out of the corner of this room. There has been pushback by several states against the Social Work Compact due to inclusion of a requirement for passage of a standardized licensure exam. That is a valued discussion, though not the focus of this blog article.

The immediate concern to compact passage involves those states with what may be considered as more liberal rather than conservative practices or vice versa depending on your viewpoint. To practice in any compact member state, social workers must abide by laws, regulations and scope of practice of the state in which the client is located. As a result, concern has been expressed over any potential liability of workforce members should their interventions be counter to emerging legal practices for the state. Precedents for these concerns have already been defined through legal actions against our interprofessional colleagues across medicine, nursing, and other behavioral health professionals in some states. There are equal concerns about practitioners contacting ICE to report patients who present for treatment that may be undocumented. These actions are counter to professional standards previously addressed in my blog article on this topic several months ago, To Report or Not Report: Mandatory Duty to Warn for Case Management (though applicable intel for all professions). Of primary concern are states that:

- Do not allow abortion or limit emergent medical attention to the mother in emergency situations where the health of the individual is at gross risk (e.g., miscarriages)

- Do not allow or limit provision of resources to minors of their families for the purpose of obtaining out of state abortions in the instance of child abuse or exploitation

- Do not allow or limit provision of resources to adults or their families for the purpose of obtaining out of state abortions for any reason including for rape, incest, or other sexual assault or intimate partner violence; this might also include providing of the morning after pill or other medical treatment guidance.

- Have restrictive reproductive health limits for treatments (e.g., in vitro fertilization), or other medical treatments (e.g., stem cell transplants).

- Do not allow or limit gender-affirming care or the provision of information on such care to minors

- Do not acknowledge transgender rights and access to necessary care

- Do not acknowledge the value of concordant care across vulnerable and traditionally marginalized populations

- Enforce cuts to Medicaid and Medicare Advantage plans that limit access to or deny services that promote patient, family, or care-giver self-sufficiency and wellness (e.g., durable medical equipment, home health care, skilled nursing facility)

- Limit access to substance use disorder and medically-assisted treatments

- Do not allow use of language specific to diversity, equity, inclusion, belonging, accessibility, health equity, social justice and any aligned terminology

There are endless examples of other concerns, along with emerging legal cases against the workforce. Some states are engaged in lawsuits against practitioners for denying emergent medical care to patients hemorrhaging from miscarriages, with mortality rates unnecessarily rising from this level of negligence. Maternal deaths in Texas have risen by close to 60% following the abortion ban. An Ohio women who suffered a miscarriage at 22 weeks of gestation in her home and sought treatment at a local hospital, initially faced criminal charges. As if the trauma of her health experience was insufficient, she was then charged with a felony; a judge ultimately dismissed the case. There are countless other similar situations.

Moving Forward

As noted in my prior blog article, there have always been caveats to a professional’s legal and ethical obligations when religious, cultural, or other values and mores have the potential to obstruct effective care of a patient. In those situations, a safe handoff to another professional is indicated. These caveats carefully balance patient right to autonomy, self-determination, and do not harm with practitioner values. Yet, despite these protections, compact expansion has still gotten caught up in the latest values- and cultural-backlash.

Mental health demand in the U.S. has never been higher. Given the pent-up demand for behavioral health and other services, social workers and other professionals must be able to practice across state lines. Compact expansion and social work ethics must not be allowed to suffer due to these current realities.